In asymmetric games, we have to care about making all our different starting options fair against each other in addition to making sure the game in general has enough viable options during gameplay. That means each character in a fighting game and each race in a real-time strategy game should have a reasonable chance of winning a tournament in the hands of the right player. For collectable card games and team games like Guild Wars, World of Warcraft’s arenas, and DOTA2, at least “several” possible decks, class combinations, and heroes should be able to win tournaments. Furthermore, we'd hope that there's never a card, class, or hero that must be part of your composition, and that there aren't any that are so bad that they can't reasonably be used in any winning composition. We'd hopefully have much higher standards than even that, but that's just a minimum level of competence to shoot for. (This assumes no player-run banning system either; that's already below the minimum level of balancing competence to shoot for.)

There are some ways we can affect the chances of our success in balancing before we even get to the balancing part. It has to do with having a solid foundation, or a shaky one.

Self-Balancing Forces

Self-balancing forces fix balance problems without us having know exactly what those problems even are. If you're in charge of balancing a game, it probably has some problems you know about and some problems you don't know about. The ones you don't know about are the bigger danger, so anything that reduces or eliminates those is very valuable. (It reminds me of The Sheathed Sword.)

The fighting game Guilty Gear is a good example of this technique. It has an extremely diverse set of characters, yet somehow manages to be pretty well balanced. I covered how that's possible in this article. The short summary is that they built in failsafes such that every character has protections from getting abused too badly. Every character has guard meter, progressive gravity, green blocking, burst, and more.

Guard meter helps stop combos from going on forever by making your hitstun get shorter and shorter as you get hit by more moves in a combo. Likewise, progressive gravity ends combos eventually by making you fall faster and faster while you're being air juggled. Green blocking lets you push attackers away when you block, which allows you to avoid potentially inescapable lockdowns. When all else fails, the burst feature lets you escape any combo about once per round.

Each of these features solves balance problems that the designers didn’t even know they had. They don't have to know how to do perfect trap of blocked moves that you can never get out of. They don't have to know how to do a juggle combo that goes on forever. They've solved all these problems generally and globally, without needing to know exactly which cases might have caused a problem. This technique is difficult to apply to many games, but it's very valuable if you can.

A Shaky Foundation

You can fail before you even start by having way too many characters or way too much customization.

Yomi has 20 characters, which means it has 190 matchups in the 1v1 mode, not counting mirror matchups. That's very difficult to balance, but possible. You can read about that process here. Imagine if it had 100 characters though. Five times as hard to balance? Actually that's over 26 times the number of matchups. The difficulty in balancing isn't linear though, so it's probably 100x as hard to balance. A card game like Yomi or a fighting game like Street Fighter doesn't need anywhere near 100 characters. 20 or 30 is already a lot, so a game with 100 is setting itself up for balance failure from the start.

Customization is also a dangerous thing. Similar to having many characters, having lots of customization feels like it gives players more options. Not more viable options though, it actually tends to give them far fewer. Consider Yomi again. It has 20 fixed (non-customizable) decks, each with 55 cards. All 20 decks are tournament viable. What if we took the equivalent number of cards (55*20 = 1100 cards) in a different game and allowed full customization to create any 55 card deck you wanted. That game would have over 377,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible decks. That's more decks than there are grains of sand on Earth. More than the number of stars in the galaxy. In fact, it's more than the number of particles in the observable universe. So that's what we're balancing?

What do you think the chances are that the top 20 of those 377,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 decks are about the same power level? I think it's about 0% chance. In all likelihood there is only one playable deck, or maybe 2 if you're lucky. If you fixed those one or two decks, you would not find 20 decks of equal power level just below it, either. At any given time, at most 1 or 2 decks (or about 0% of total possible decks) would be viable. This kind of massive customization is almost inherently unbalanceable.

Don't try to fix this by having players ban each other's decks or characters. That's a cop out and it feels terrible to identify with a character, to learn its gameplay and have it fit your personal style, then to be told it's banned for some reason. Don't do that to players. Instead, do the hard work of making your game actually balanced and start with a foundation that has some hope of ever being balanced enough that several different starting options are fair. Let's get to the process of achieving that now.

Playtesting and Course-correcting

Suppose you have a game to playtest. You designed a diverse set of characters / races / whatever and made each one coherent and interesting. During that design time, you should have the confidence that you’ll sort out the balance problems in playtesting. All the theory in the world will not save you from playtests, so there's no way you could have gotten it perfect (or even acceptable) yet.

You need to start tuning the game, and react and learn as you go. Do not let a producer turn tuning into a fixed list of items that you are accountable for checking off, one by one. It’s an organic, continuous process that keeps going until you need the ship the game. Playtesting lets you discover things you couldn’t have predicted ahead of time, and you should be open to those discoveries. The goal isn’t to make the exact game you originally envisioned, because your original vision did not take into account all the things you learned from development and playtests. When you or the testers discover nuances or unexpected properties, you have the chance to build around those and incorporate them into the game’s balance.

The Tier List

During the balancing of Street Fighter, Kongai, and my card game called Yomi, I used a similar approach with playtesters. I think this approach doesn’t really depend on the genre, and the key idea is managing the tier list.

The term “tier list” is, I think, a term from the fighting game genre. It means a ranking of how powerful each character is from highest to lowest, but it also accepts that such a list cannot be exact. Instead of ranking 20 characters from 1 to 20, the idea is to group them together into “tiers” of power.

A linear list would be bad for two reasons. First, players might think characters X, Y, Z are about the same power level, but would have to list them as something like 6th, 7th, and 8th. That creates data incorrect data that's indistinguishable from if they think character X is far better than character Y. Second, a linear list would not give you an idea about the gaps in power the players are experiencing. Is the #1 ranked character much more powerful than all others? Or maybe the #1 and #2 are similar in power, but they are both higher than the rest? Or maybe #1, #2, and #3 are similar in power? A tier list will show you this, but a linear list won't. Use a tier list, meaning each tier is the set of characters who are a similar power level to each other.

Remember that if a divine being handed you a 100% perfectly balanced game, that players would still make tier lists. You should accept the existence of these lists from players as a given, and its your job to manage this list. In Kongai and Yomi, I even gave the players a template for the tier list that is most useful for me as a designer. First, I tell them to think of three tiers: top, middle, and bottom. Then I tell them about the two “secret tiers” that I hope are empty.

0) God tier (no character should be in this tier, if they are, you are forced to play them to be competitive)

1) Top tier (don't be afraid to put your favorite characters here. Being top tier does not necessarily mean any nerfs are needed)

2) Middle tier (pretty good, not quite as good as top)

3) Bottom tier (I can still win with them, but it's hard)

4) Garbage tier (no one should be in this. Not reasonable to play this character at all.)

My first goal of balancing is to get the god tier empty. Of course some character will end up strongest, or tied for strongest, and that is ok. But a “god tier” character is so strong as to make the rest of the game obsolete. We have to fix that immediately because it ruins the whole playtest (and the game). Also, the power level of anything in the god tier is so high, that we can’t even hope to balance the rest of the game around it.

My next goal is get rid of the garbage tier characters. They are so bad that no one touches them, and it’s usually pretty easy to increase their power enough to get them somewhere between top, middle, and bottom. If they are somewhere in those three tiers (which gives you a lot of latitude actually), at least they are playable.

Public Tier Lists

I really like it when playtesters all see each other’s tier lists. The debate this spawns is very useful for me to read (or overhear in person) and for the playtesters to sort out their ideas. Sometimes when someone put a character unusually high or low on the list, I dug deeper to find out that player really did know something most of the rest of us didn’t. Other times, that player is just crazy and the rest of the testers are happy to point that out. It’s also good to see what kind of consensus the testers come up with, like if they all rank a certain character as the worst, for example.

The biggest landmark moments in each of the games I balanced was when the tester communities consistently gave tier lists with no characters in the god tier or garbage tier. Once you’ve achieved that, the next goal is to compress the tiers. That means that you want the difference between the best and worst characters to be as small as possible. Notice that that means even if you have the same characters in the bottom tier that you did a month ago, you might have dramatically improved the game if all those “bad” characters are really only a hair worse than the tier above, rather than way worse.

Adjusting the Tiers

In all the games I balanced, I used the same approach of letting the top tier set the benchmark power-level. In Street Fighter, I already had an established top tier as a starting point from the previous game, but in Kongai and Yomi, it was somewhat accidental who ended up in the top tier. But early on, after the god tier was removed and it was pretty clear which characters / decks were top, I allowed that to be the target power level. In other words, the characters in that tier are “how the game is supposed to be.” Again, I didn’t plan exactly who would be here, but I accepted how it ended up and worked with it. So if the top tier is the target, it’s the bottom tier you should adjust the most. If the top tier is the intended power level, you don’t really want to mess up the good things you have going there. Instead, boost the bottom characters up and compress the tiers as much as you can, so you get the worst characters just barely below or equal to the best characters.

There are some psychological factors that I saw over and over again while making these adjustments. The first is that whenever I make a move or character worse (aka “nerfing”), players overreact. Sometimes that top tier creeps a little too high in power, or an otherwise average character ends up having something unexpected that’s crazily good, or a character has a move that really reduces the strategy in the game and needs to lose that in exchange for gaining something else. There’s lots of reasons for nerfs.

I’ll use some made-up numbers to convey the general idea here. Imagine a move is at power level 9 out of 10, and that’s just too good for that character. Time and time again, I saw that if I made the power level an 8 out of 10, playtesters would complain that the move was worthless and put the character down at least one tier. This happened consistently, and even in the cases where 8 out of 10 was still too powerful and it really needed to be a 7. For some reason, players in every game seem unable to grasp the concept that a top tier character who is made slightly worse can still be a top tier character.

This is one of the cases where I think you just can’t listen to the playtesters. Ignore their first reactions to nerfs, let them play it more and get used to it, let them see if they can still be successful with the new version of the move, then take their feedback on that move or character more seriously.

The other psychological effect to know about is what happens when you increase a move’s power. I learned about this Rob Pardo’s lecture on balancing multiplayer games at the Game Developer’s Conference, and I tried it on all the games I balanced, and I think Rob is right. He said that if you have a move that you’re not really sure how to balance, make it too powerful. If you make it too weak, then you run the risk of no one using it at all. Then, when you slightly increase its power, none of the testers will notice or care. They already decided that move is weak. Then if you make it slightly more powerful still, they still won’t care. Even when you inch it up past the reasonable level of power, it’s hard to get it on people’s radar and that makes it really hard to know how to tune the move.

Instead, Pardo said to start with the move too powerful. Then everyone will know about it and care about it. I did exactly this with T.Hawk, Fei Long, and Akuma in Street Fighter HD Remix, because I had trouble figuring out their power levels. Each one of those characters was the best character in the game at some point in development, and that meant I got lots of feedback from testers about these characters. It also gave me a sense of where the top of the scale even was. Sometimes my “too powerful” versions of a character would end up waaaaay too good, or sometimes just barely too good. By knowing where the upper limit was, it helped me pick appropriate power levels more quickly. That said, I did have to deal with the inevitable cries that follow all nerfs, but that just goes with territory here.

Illusions in Tiers

Another point from Rob Pardo’s speech on multiplayer games was not to balance the fun out of things. I’m very conscious of this as well. Don’t just think about the game as some abstract set of numbers that has to line up. You also have to think about how people will perceive it and whether it’s actually fun. Pardo said that he likes the player to feel like the tools they have are extremely powerful, even though they are actually fair.

An example of this in one of my games is Tafari, the Trapper in Kongai. Tafari’s main ability is that the enemy cannot switch characters while fighting him. Switching characters is one of the game’s main mechanics, so fighting him is like playing rock, paper, scissors with no rock. It seems, at first glance, ludicrously powerful. But from the start, I gave Tafari several weaknesses and he loses many fights if he ends up having to fight on even footing. He’s best when you bring him in against an already-weak character to finish them off.

I knew Tafari was not too powerful. I tested him with many experts and they tended to rank him as middle tier once they got the hang of him. As we added new testers over time, probably nearly 100% of them claimed that Tafari was too strong. I refused to change him though and after a year of testing, the best players still ranked him as middle tier, while inexperienced players still ranked him as top. Tafari is an illusion.

I’m telling you this because you have to be very careful with feedback in cases where you intentionally made something feel more powerful than it actually is. It’s a success if you can pull that off though, because Tafari makes the game more interesting, creates lots of debates, and at the end of the day, he is balanced.

Counter Matches

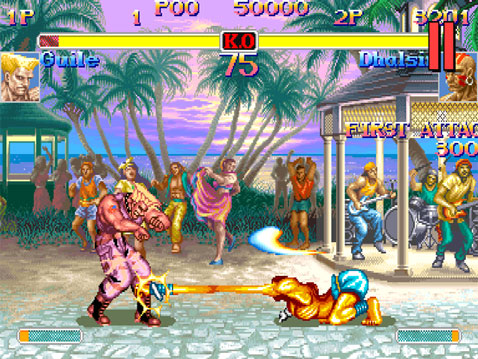

In addition to the tier list, you should also be thinking about all the specific matchups. Street Fighter HD Remix, for example, has 17 characters and 153 possible matchups. For the version of Street Fighter before HD Remix, experts tend separate the characters into four tiers (none of them are god tier or garbage tier), and they place Guile in the respectable second tier. Even though that means Guile’s power level is acceptable, he is severely disadvantaged in two specific matches: Vega and Dhalsim. Is it ok that an overall good character gets countered by two specific characters? Not really.

If these were weapons in an FPS or units in an RTS or characters in team-based fighting game, then it might be acceptable. You pick up weapons in an FPS after the game starts, so their balance doesn’t need to meet the hard requirements of an asymmetric game. And units in an RTS and characters in team-based fighting game are examples of local imbalances, which are fine (it’s the races and teams that need to be balanced). But in Guile’s case, you lock in your choice of Guile at the start of the game, then you are stuck with him the entire game, so it really is a problem if he has some bad counter matches, even though players rate him fairly highly overall.

It’s really tricky to adjust anything in an asymmetric game though. How can we help Guile in just the Dhalsim match without affecting all the other matches? There’s no easy answer here, but I advise you to really solve the problem, rather than copping out.

My real solution to this problem was two-fold. First, for reasons unrelated to this particular match, I changed the trajectory of Guile’s roundhouse flash kick. This happened to help a bit against Dhalsim’s fireballs, so we’ll count that as a lucky accident. Second, one of Guile’s problems is that Dhalsim’s low punches can go under Guile’s Sonic Boom projectiles and hit Guile from across the screen, with no repercussions. I changed Dhalsim’s hitboxes so that Dhalsim now trades hits in this situation, rather than cleanly hits. This change has virtually no effect on any other match, so it’s a real solution to the problem.

A cheating solution would have been to special case this match and give Guile more hit points. This sounds attractive because you don’t have to worry about messing up other matches, but this non-solution feels really artificial. It messes with players’ expectations and intuitions about how many hit points Guile has.

A similar cop out would be to create a giant table in an RTS of every unit versus every unit and special case how much damage they all do to each other. Again, it messes with player intuition about how damaging each unit is, and creates and invisible, wonky system. I know you’re going to be tempted to use these types of special case solutions when balancing asymmetric games, but try your hardest to avoid them.

Conclusion

Start your design with some self-balancing forces and fail-safes if you can. Then go wild and create all your game’s diversity, then start the long road of playtesting. As you learn more from playtesting, change your course as you go. Start keeping track of tiers, first by fixing the god tier, then by fixing the garbage tier. Then compress the tiers so that even the bad characters are only slightly worse than the best characters. Finally, fix all the counter-matches you can by actually solving the puzzle, and avoiding cop out solutions.