Yomi is a fighting game in card form. It's a tabletop game, an online game, and it's on iOS too.

My original inspiration for creating Yomi was my extensive experience as a tournament fighting game player. I like the interesting situations and dynamics that come up in fighting games like Street Fighter, and I like the idea of having lots of characters and lots of matchups that play differently. I wanted to capture the essence of that for people who don't have the dexterity to play fighting games. (And as an alternative game for those who do!)

I also wanted to create an efficient game. A good strategy game that could be played at a tournament level, yet at the same time as simple as it can be and with as few components as possible. That meant focusing on just what I needed to make the game work, and removing everything else that I could. For example, it would have been natural to give each character at least 15 different abilities, but I chose to limit it to just 3 or 4 per character. I could have used more components than just a deck of cards, but I limited the design to just one deck per character with no other pieces.

And yet, I also needed the game to be such an excellent strategy game that experts could play it thousands of times at the tournament level and not get tired of it. I'll explain what went into making such a game.

Rock, Paper, Scissors: Everything Has A Counter

Yomi uses a core mechanism of rock, paper, scissors to resolve each combat. You might be thinking that rock, paper, scissors is shallow and so it means a game that uses it wouldn't be interesting, but that's not a fair statement. Just about every competitive game has a form of rock, paper, scissors in it. All that means is that things beat each other and everything has a counter. The alternative would be...some things don't have a counter? That would be a problem.

In Starcraft, individual units counter each other in a rock, paper, scissors-like way. Also, various strategies such as early rush, heavy econ, and moderate builds counter each other in that same way. In a first-person shooter such as Halo, rifle (rock), grenade (paper), melee (scissors) counter each other. In a fighting game such as Street Fighter or Virtua Fighter, attack (rock), block (paper), and throw (scissors) have a similar relationship. That's exactly what I used as the basis of Yomi. I also added dodge as an option similar to block, but with different payoffs.

One reason you might have the connotation that rock, paper, scissors is bad is that if you literally play a game of rock, paper, scissors, you have very little to go on when you decide which move to use. Every option is functionally the same. You can look for patterns your opponent might unconsciously fall into, but that's all you have to work with. In competitive games like StarCraft, Halo, Street Fighter, and Yomi, you have tons of information to work with though. There's a lot of tells, there's a lot of reasons an opponent might choose one option over another in a certain situation, and there's a lot of nuance.

Using this core mechanism really just means that we know each basic type of move has some counter and that we can communicate to the player an easy way to resolve combat. If we had 20 types of moves that require looking up a chart to know what beats what, it would no longer be easy to understand and it wouldn't necessarily add any strategy anyway.

Double Blind

Play your combat card face down, at the same time as your opponent.

Your card

Opponent's card

A double blind decision is one where you decide something at the same time as another player. Neither of you know what the other will do until you're both committed. Double blind decisions are a very useful tool in fighting against solvability in games. Games with perfect information and no randomness inevitably degenerate into more and more memorization until they eventually become 100% memorization once they're completely solved. They "break" more easily and sooner than games with some hidden information, randomness, or something to break up the rigidity.

Reveal Simultaneously

(attack beats throw)

Double blind decisions are generally a good idea in a competitive strategy game for those reasons, but that's not the only reason to include them in Yomi. It's also very fitting for the fighting game theme. You might think that fighting games have perfect information because both players can see the same screen at all times and there's nothing hidden. You always know exactly which options and resources your opponent has and they know the same about you.

Fighting games are actually double blind though because of the speed of the gameplay. At the moment when you do a move, you usually do not know what the opponent is doing exactly. Human perception is only so fast, so you’re acting on information that’s a few sixtieths of a second old (fighting games are measured in frames, which are sixtieths of a second). At the exact moment you jump, you do not know if the opponent threw a fireball or not unless they threw it several frames ago. Some of your moves are made on reaction, but many of your moves are essentially made in a double-blind situation.

Rock, paper, scissors is inherently double-blind, so that's a good fit here. But we really need to add something to make this all actually interesting. You need more to go on to have reasons to do one option over another and to have some basis of predicting how your opponent will act.

Unequal And Unclear Payoffs

The first step to making a rock, paper, scissors mechanic interesting is to have way different payoffs for winning with each option. For example, if winning with rock gives you $10, winning with scissors gives you $3, and winning with paper gives you $1, there's a least a little more to it. Your personality (or your opponent's personality) is more likely to be a factor. There's also risk management to consider. Imagine if you play a series of rock, paper, scissors with those payoffs and that you'll lose when you drop to $0. Now imagine how you'd play if you only had $10 left. If you lose to the opponent's rock, it's worse than just losing $10: you also lose the entire game. So now you have to adjust how you play to protect even more against the possibility than you usually do. But you can't just play scissors 0% of the time there either; that's predictable and exploitable.

It's a lot better if the payoffs for each option are unclear. In the example above, it's trivially easy to know how much better the payoff is for rock than paper: it's exactly 10 times better. To make it a lot more interesting, the payoffs should be extremely difficult to compare or even to compute in the first place.

You'll need to use a skill called valuation: the ability to judge the relative value of pieces and how they change over time. The ability to make on-the-fly judgments about what things are really worth is an interesting skill to test in many competitive games. Ideally these judgments are so complicated that you must use your intuition to solve them and knowing the exact answer is virtually impossible. The alternative would be that you pre-compute everything and rely on memorization. Using intuition is just more fun though. Also, the harder it is for people to ever compute exact answers to what various moves are worth, the better job we're doing as designers to prevent or delay our game from being solved.

The Yomi: Fighting Card Game System

Now we need a system that is so complicated that its exact paper-rock-scissors payoffs can’t even be calculated, and yet so simple that anyone could play it. Here's how that's possible.

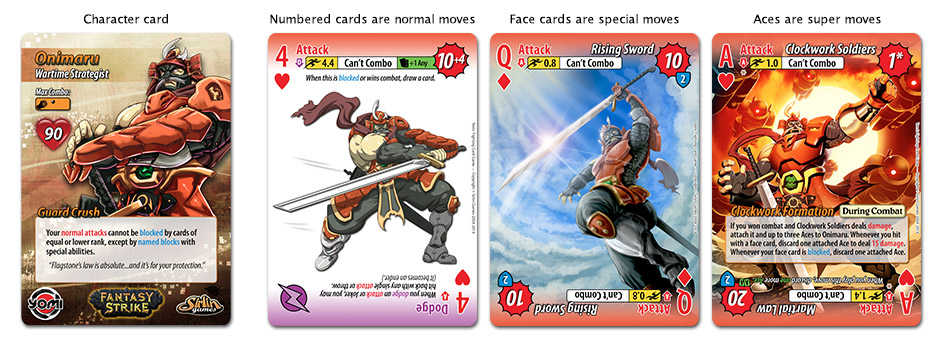

Each player has a deck that represents their character. These are fixed (non-customizable) decks with 52 poker-type cards, 2 jokers, and one character card. These decks use standard playing card notation and they have extra information on them for the Yomi game. The numbered cards represent normal attacks, the face cards are special attacks, the aces are super attacks, and the jokers can rewind time to undo a combo that would hit you.

Established Conventions Convey Information Quickly

I deliberately used the conventions of a poker deck in order to instantly convey a lot of information to the player. When you see a queen that is a Dragon Punch card, you know right away that that there are three more of them in your deck. You also immediately know how likely you are to draw a super move (there are four aces in your deck). You probably also have at least some intuition about how often pairs and straights come up if you’ve played any other cards games at all.

There's a lot of patterns in Yomi decks that help you learn the contents of your deck very quickly. Your 2 attack does 2 damage, your 3 attack does 3 damage, your 4 attack does 4 damage, etc. There's also a speed stat. For several characters, their 2 is speed 2.6, their 3 is speed 3.6, their 4 is speed 4.6, etc. The .6 part is consistent across all their normal attacks. A different character might have the same pattern, but .4 instead of .6.

Because I need to convey so much information and make it seem natural, it was very useful to piggyback onto a structure everyone already knows—two of them, actually. Yomi contains Street Fighter-like moves/characters as one bundle of information that a lot of people are familiar with as well as the playing card structure that almost everyone is familiar with.

Two Options Per Card is Efficient

It's comfortable to hold a hand of 7 cards, and to maybe go up to 12. Sometimes you'll be down to very few cards though, like 3 or 4. How can we make sure you have access to enough moves at any given time with that number of cards? Yomi cards usually have different options on the top and bottom. For example, Grave has 24 block cards in his deck, which is 44% of his 54 card deck. That's really high and ensures you'll have blocks when you need them. But every one of those blocks can also do something else: either attack, throw, or dodge. Having two options on most cards is an efficient way for us to give you access to enough moves.

Double-blind Combat

Each combat, you play one face down card at the same time as your opponent. The side of the card closest to your opponent is the option you chose (if your card had two options). I already covered why double-blind combat matches the flavor of fighting games and why it helps prevent the game from being too solvable.

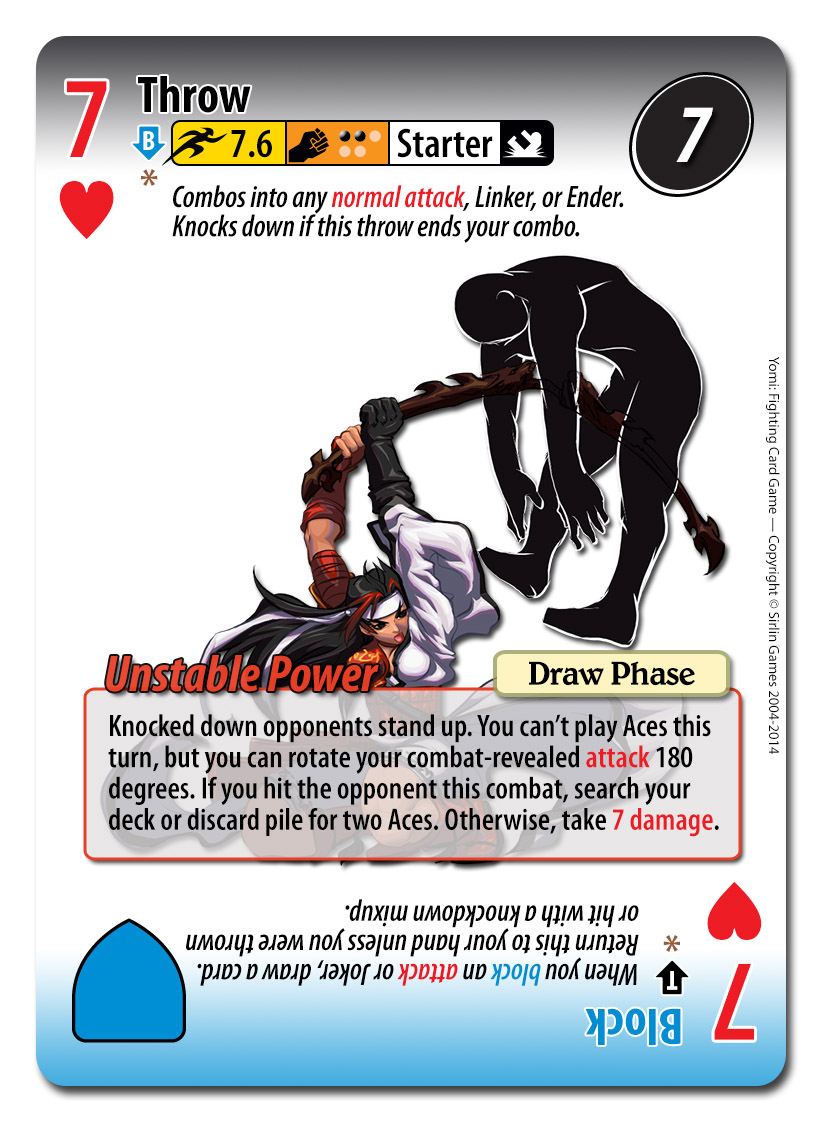

Combos

Combos are a big part of fighting games, and they're a big part of Yomi too. Yomi has a combo system where normal attacks chain to each other in increasing sequential order, such as a 2, 3, and 4. Normal attacks can also generally combo into special and super attacks. That's governed by each move's combo type: starter, ender, linker, and can't combo. A starter has to be at the start of a combo—you can't use it if you already started your combo with something else. And ender will end your combo, not allowing you to play any more hits. A linker is very versatile, allowing you to combo into it and combo after it. A can't combo move is basically a starter and and an ender: it has to be the first hit of your combo and it's also the last.

Finally, each character also has a certain number of combo points. Each move says how many combo points it has (each move also says exactly what it combos into, by the way). Combo points limit how big your combo can be. Some characters can do big combos while others can't.

The combo system is fun and flavorful. It gives you a goal as a player to build up to a big combo. It also creates a lot of hand management decisions so there's a lot of skill involved here. Should you use a dragon punch move in a combo or should you use it as your combat card? Should you do a full combo now to maximize your damage, or a smaller combo that lets you keep more cards in hand? The right answer depends on a whole lot of factors.

Powering Up

The power up mechanic also adds difficult decisions to the game. At the end of each turn, you have the option of discarding pairs, three-of-a-kinds, or four-of-a-kinds to search your deck or discard pile for either one, two, or three aces respectively. Is it worth it to break up a pair of fives to use one in a chain combo instead of trading in the pair for an ace? The answer is unclear and depends on a lot of things about the current situation.

Attack, Throw, Dodge, and Block Have Unequal Payoffs

1) Attack

Usually, the best way to deal damage is to win with an attack. (If you both attack at the same time, the faster one wins). When you win with an attack, you can then perform a combo by playing more cards from your hand.

2) Throw

Winning with a throw is very similar to winning with an attack, except that your resulting combo is usually not as good because of the way the stats on the throws are designed. Also, throwing a blocking opponent is the only way to get rid of their block cards.

3) Dodge

Winning with a dodge lets you avoid an incoming attack completely, and then lets you hit back with any single attack. You can’t do combos though, so do your strongest attack, hopefully a super.

4) Block

Winning with a block lets you return your block card to your hand and draw an additional card. This is your best way to build up more cards in your hand.

Unclear Payoffs

As I explained earlier, the payoffs are unclear. How good is drawing an extra card when you block an attack? It depends how many cards you have and somewhat on how many cards the opponent has. It depends on which character you are too, and what your life totals are, and a lot more. How good is winning with an attack? It depends on how big of a combo you can do. How bad is it if you try to throw but get hit by an attack? It depends on what kind of combo your opponent has built up, and you only have indirect information about that. Would it be twice as bad to get hit by their combo compared to letting them draw a card? Three times? One half times?

Players Naturally Develop a Pattern

Even though the payoffs are unclear, a definite pattern develops in how people tend to play. This exactly the property we want because it sets up the mind-games perfectly. If you are low on cards, I know you want to block to draw more, and you know I know. If I just traded in several pairs for aces, you know I’m itching to dodge so I can hit back with a super attack, and I know you know. Will you follow “the script” and do the obvious thing? Or will you go to the next Yomi layer and do the counter to the obvious thing? Or to the Yomi layer after that and counter the counter? These types of mind-games occur in just about every worthwhile competitive game, and the Yomi card game lets you practice these situations and practice reading opponents.

In case you think you can "just play optimally" and ignore what the opponent is doing, please read this article on solvability in games. It explains exactly why high level Yomi play always involves reading the opponent, even if both players are extremely good. Especially if both players are extremely good.

Special Abilities Make Payoffs More Unclear

There are more nuances. Each character has a special ability on thier character card as well as two more special abilities that appears in the deck. For example, Jaina's character ability lets her pay 3 life (starting life: 85) to return most kinds of attacks she played that turn to her hand. This is yet another valuation test, constantly asking you how much you think each card is worth. Also, Jaina's Unstable Power ability lets her gamble with an increased chance to win combat and a great payoff if she does, but she'll get burned if she doesn't.

These abilities make computing the exact payoffs even more difficult because they manipulate so many different kinds of things about the game. Some improve the quality of cards in your hand, others make the opponent discard, others increase the speed of your attacks, others let you teleport out of a bad guess, and so on.

I could have put special abilities on every card, but I don’t want the game to be overwhelming. Even with just one ability on your character card and two or three others in your deck, there is enough going on to make it very unclear what the smartest thing to do at any given time is, while keeping the game easy to play.

20 Characters

It's challenging to balance different characters such that they're all fair against each other, but it adds so much when it's done right. Players can identify with a certain character because they like that character's personality, the way they look, the playstyle they offer, or a combination of those things. Having characters that all play differently also creates a many different possible matchups, each with their own dynamics to explore.

The first version of Yomi had 10 characters, which creates 55 different matchups in the 1v1 mode. There's currently 20 characters, which creates 210 matchups. How to balance all that is the beyond the scope of this article, but you can read about it here.

Conclusion

Yomi simulates a fighting game by having you decide your move in a double-blind fashion with your opponent. It has unclear and unequal payoffs so it's very hard to compute perfect play, and it rewards your on-the-fly skills at valuation (knowing the true value of various cards as the game progresses) and yomi (reading the opponent's tendencies). It also lets you do fun combos.

Because Yomi is so boiled down to the essentials, I think it’s an interesting way to learn about valuation and yomi (as in reading others, pattern recognition). I think these are the two fundamental skills of competitive games, so I hope that whatever you learn from playing Yomi will help you in all your competitive gaming exploits adventures.

Yomi has been played online and in person for many years and in many tournaments. It ended up being all that I hoped for. It remains a great strategy game at the highest level of play. If you're interested in how well balanced it is, check out this article about the game's balance.

You can play it in tabletop form, online, or on iOS.